What the ... ?

I receive photos of weird and mysterious bugs frequently, often with the subject line, “What is this?” You, my faithful readers, also have a standing invitation to send me photos and questions by clicking on my name at the bottom of this newsletter.

I’m going to steal a page from Paul Pilon’s Perennial Pulse playbook and do a “What is this?” game. Since I’m not a gentleman like Paul, I’ll call this game based on my frequent initial reaction.

This week’s “What the ... ?” creature comes courtesy of my friend Brett Link:

These critters congregated in large numbers on a crape myrtle trunk. (Photo credit: Brett Link)

Answer appears at the end of this newsletter. Read on. [See how I got you hooked?]

Oil or soap for scales?

Scale insects are my specialty. These’re tough little buggers to kill. Systemic insecticides work great for some species, but not for those that feed on woody tissues. Sprays work best when hatchlings (or crawlers) are coming out from their mamas’ shells.

For years I recommended horticultural oil and insecticidal soap for sprays, and thought they worked equally well against all species. A recent article by Cliff Sadof of Purdue University and his graduate student, Carlos Quesada, in HortTechnology (October 2017, volume 27, page 618-624) shows me that I need to update my recommendation.

Carlos and Cliff did a series of lab and field studies on two armored scales (pine needle scale and oleander scale) and two soft scales (calico scale and striped pine scale). Oil and soap, both applied one time at 2%, killed 67-93% of crawlers of all four species; that’s a pretty good level of control. But both oil and soap became less effective as the scale insects settled comfortably and grew. Spraying oil or soap against adult scales was as good as spraying water. No surprises so far. The basic recommendation still applies: You need to spray against crawlers to achieve the best control.

Here’s the good part: In the field studies, oil was more effective against settled armored scales, whereas soap was more effective against settled soft scales. Who knew there are differences between oil and soap on which group of scale insects they are most effective against? I didn’t!

Carlos and Cliff speculated that the difference arises from the chemical properties of the chemicals and the scale insects. Both oil and soap kill mainly by suffocation, but, chemically speaking, soap is polar (so it likes to stick to another polar object) and oil is non-polar (it is repelled by a polar object). As armored scale crawlers settle, they produce a waxy cover over their bodies within three days. Most soft scales, on the other hand, do not usually produce a thick wax layer until adulthood. Wax, being non-polar, reduces penetration of polar soap but allows penetration of non-polar oil. Skin of soft scales is polar, so soap sticks and penetrates the layer more effectively, thus doing a better job of killing soft scales.

Fascinating, isn't it?!

What about those soft scales that produce plenty of wax when they are babies, such as the wax scale? Perhaps oil works better in this case? I don't know; I will need to find out. More research!

Big, fat adult female oak lecanium scale is a common sight on oak trees in the spring. Good luck trying to kill these ladies! Kill their babies instead.

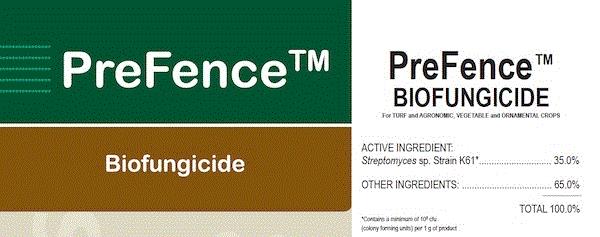

PreFence, a new biofungicide for root rots and damping-off

BioWorks introduced PreFence in mid-January. I called up Matthew Krause, a plant pathologist with BioWorks, to get the lowdown. Poor man; he had to negotiate his way through the mountains of Pennsylvania to Hershey, all the while listening to my yacking.

This is a biofungicide containing mycelium and spores of a Streptomyces bacterium, the same active ingredient of Mycostop. BioWorks introduced PreFence to better suit the needs of ornamental growers. PreFence is registered for indoor and outdoor ornamentals, turf, field crops, vegetables, mushrooms and tree seedlings. On turf and ornamental crops, PreFence can be used against root and stem rots, damping-off and blights caused by Alternaria, Botrytis, Fusarium, Phomopsis, Phythium, Phytophthora and Rhizoctonia. It can be applied through a wide range of methods that suit your needs.

PreFence works by producing antagonistic metabolites that stress pathogens and reduce diseases, which in turn promote plant growth. PreFence is OMRI-listed, with a REI of four hours.

Similar to many biofungicides, PreFence should be used as a preventive tool or as a part of an integrated disease management program to better steward our existing fungicides. It is not meant to be a stand-alone product. Bioworks recommends PreFence as a supplement to other preventive products. Preventive programs for root rots could begin with RootShield PLUS; and botrytis with a tank mix of CEASE and MilStop. Add PreFence to the preventive program, or consider chemical fungicides, if you anticipate or experience higher disease pressure (watch out for environmental conditions favorable to disease development!).

Learn more about PreFence HERE.

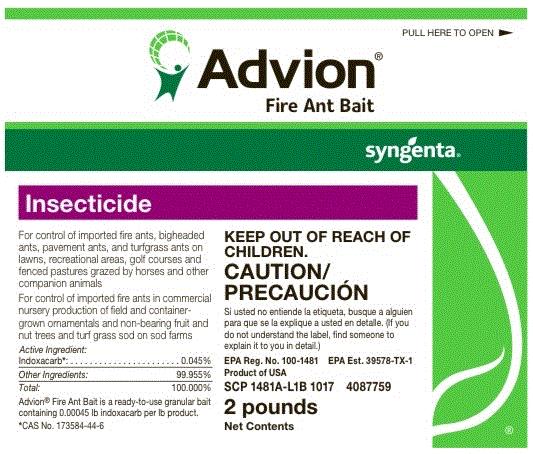

Advion fire ant bait now has nursery use

Also in mid-January, EPA approved additional registration of Advion fire ant bait for use in ornamental nurseries, sod farms, and pastures grazed by horses and other companion animals. The current label of Advion fire ant bait is HERE.

You few, you lucky few, you who are ignorant of fire ants. Turf managers and golf course superintendents in the South have been using Advion to control fire ants and other nuisance ants with great success since 2014. I’ve gained some experience with this product in the turf market since then. One of the biggest benefits of Advion is that fire ants virtually disappear from a treated area within a week. This is much faster than other slower-acting or insect growth regulator-based fire ant baits that act in weeks or months. Landscape care professionals in the South use this product in lawns of recent yankee-transplants, who want them ants gone, and quickly.

This effective tool is now available for nursery and sod growers. If you grow sod and plants and want to ship them outside of the fire ant quarantine area, you still need to adhere to USDA’s fire ant quarantine treatment procedure. Advion is not on the current list of approved insecticides (last updated in 2015). Advion, however, can be used to reduce fire ant population in and around the nursery to reduce the chance of fire ants invading the containers, supplementing insecticides incorporated or drenched through the medium.

I love fire ant baits. They are easy to use, effective and safe. There’re several things to keep in mind, and these also apply to Advion. Fire ant baits are formulated with corn grits coated with insecticide-laced soybean oil. Fire ants ingest the oil, and pass the oil among their nest mates in a behavior called trophallaxis (this is how a few intoxicated ants can doom the entire colony). Fire ants love oil, so they will actively seek out the baits and carry the baits home to even the most difficult-to-reach mounds (e.g., under the sidewalks). Oil can become rancid and less attractive to ants; make sure y'all use fresh baits each time or store them for only a short time in a cool, dry place. Apply baits when ants are actively foraging, and when rain is not forecasted. I usually leave some potato chips on the ground; you know ants are foraging if you find them on the chips after a few minutes. Also, for toxicant-type fire ant baits, like Advion, I recommend two applications (spring and fall) per year.

By the way, if y'all hear someone talking about killing fire ants by feeding them straight (i.e. not poisoned) corn grits, do me a favor and whack them on the side of their heads. This is one of those wacky, annoying “remedies” that just won't die. The idea is, similar to feeding rice to pigeons, if fire ants swallow grits and drink water, the grits will expand and *poof*, they explode. Now, fire ants only drink. How do they swallow grits? Silly wack job, grits are for people.

And the mystery bug is ...

Barklice; or to the bookish entomologists, the psocids. This one is perhaps Cerastipsocus venosus. (Okay, that’s my best guess. There are about 250 species in North America. Like my wife’s cousins, I don't know them all by name.) Some of its cousins feed on glue in old books; those are called booklice. I've seen barklice on various evergreen and perennial trees just about any time of the year. At times, they may spin web to cover their colony. Most of the times, these critters are wingless like those shown on the pictures; winged individuals are also common. They feed on algae, fungi and lichen on tree bark and do no harm to the trees. Not a pest but a great curiosity.

My better half just walked in with some shrimps from a guy selling them under a tent by the side of the road. No, no, he is totally legit; he got a logo and name cards and all. Y'all really can't pass up fresh shrimps right off the dock in McClellanville, South Carolina. So, how ‘bout some shrimp and grits for dinner?

See y'all next time!

JC Chong

Associate Professor of Entomology at Clemson University

This e-mail received by 24,469 subscribers like you!

If you're interested in advertising on PestTalks contact Kim Brown ASAP!