Redheaded flea beetle

The rain has stopped. Summer marches forward once again with its full complement of sun, humidity, sweat, gnats and deer flies. Welcome to South Carolina’s coastal plains!

I don't have to wait for the rain to stop to visit some of my growers and landscape care professionals. Without the rain, however, I can get better pictures of my favorite (or most hated depending on your perspective) creatures and have a collage of “What the …?”

I visited a nursery yesterday to troubleshoot some redheaded flea beetle problems. I guess “some” is an understatement because what I witnessed was devastation.

Adult redheaded flea beetles created shot holes on these Hydrangea paniculata. Severe damage can occur. (Photo: JC Chong)

Folks in the Eastern U.S. are no strangers to the redheaded flea beetle in recent years. This is a native insect species, but its status as a pest of nursery plants has enjoyed a meteoric rise in the past eight to ten years. Theories abound on what caused the rise.

This beast has become the bane of growers of hollies, hydrangeas, iteas, salvias, roses, sedums, weigelas and many other species. These small (0.1 to 0.4 in.), shiny black, redheaded beetles are not picky eaters. They feed on hundreds of plant species. Some weeds, such as clover, lambsquarter, eveninh primrose and pigweed, are their favorites.

Adults chew holes on the leaves and larvae nibble on the roots. It’s not clear if root feeding by the larvae impacts plant growth or disease (particularly root rot) prevalence. Shot holes created by adults can be devastating. A few damaged leaves can be picked off but a plant full of damaged leaves is unsalable. Foliage feeding does not kill the plants, which will reflush beautifully next spring until the beetles return. Because the damage by adults is more noticeable, adults have been the targets of management.

Brian Kunkel of the University of Delaware has done some of the most recent and detailed studies on the redheaded flea beetle. He has produced a factsheet outlining hosts, identification, monitoring and control.

Brian reported that there are two generations of adults per year in the Mid-Atlantic region. The first-generation adults appear around 590 to 785 growing degree-days (or GDD, with a base temperature of 50F) or when southern magnolia and winterberry are in full bloom. The second-generation adults appear around 2100 to 2240 GGD. No phenological indicator plant coincides with the emergence of second-generation adults. Danny Lauderdale of North Carolina Cooperative Extension Service and I are independently verifying Brian’s degree-day models in the Carolinas and Georgia. Both Danny and I found overlapping generations in the summer, making it a bit tricky to distinguish the generations.

The most troublesome aspect of the redheaded flea beetle is the difficulty of controlling them or reducing their damage.

Research by Brian and our colleagues through IR4 suggests that foliar application of products containing carbaryl, pyrethroids (e.g., bifenthrin, cyfluthrin, lambda-cyhalothrin and tau-flivalinate), neonicotinoids (e.g., dinotefuran, imidacloprid and thiamethoxam), spinosad and diamides (e.g., cyantraniliprole) can reduce damage. I observed in my own trials the same reduction in damage by the above and additional insecticides but the protection provided by these insecticides was short-lived. The foliar application killed the adults that were present at the time of the application, but other adults invaded the same plants in high numbers (and caused extensive damage) two to three days after the treatment. I haven’t found any insecticides with sufficient repellency and longevity to protect the foliage for a long time. Growers will have to spray frequently, adding to the cost of treatment.

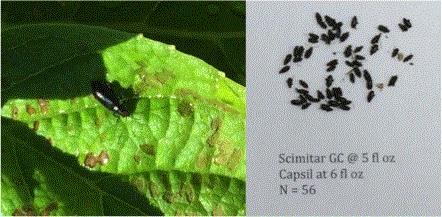

The shiny black body and red head of the redheaded flea beetles make them distinctive. Most insecticides are effective at killing adult beetles, such as these killed within two hours of one Scimitar GC application. Unfortunately, no insecticide provides sufficient long-term protection. (Photo: JC Chong)

Medium drenches with entomopathogenic nematodes (e.g., Steinernema carpocapsae), entomopathogenic fungi (e.g., Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium anisopliae), azadirachtin, pyrethroids, neonicotinoids and organophosphates can also reduce larval and adult populations. I wonder, however, how effective is drench treatment in reducing the overall beetle abundance and damage. Yes, the drench treatment may kill some larvae and (subsequently) adults but it may contribute little to the overall management program. I think most of the beetles in the production areas originate from fields surrounding the nursery where abundant weedy hosts exist. The adult beetles fly into the nursery constantly. We will not see a successful management program if we cannot reduce influx from the surrounding fields.

We don't have a good solution to the redheaded flea beetle problem. This tiny beetle has frustrated and humbled me. Our quest for a solution continues.

Solitary oak leafminer

Dowe Winchell of Greenville-Spartanburg Airport sent me several pictures of oak leafminer. Pictures were taken from a 'Regal Prince' oak.

I could tell from the pictures that these are oak leafminers, likely in the genus Cameraria. And, since they created several blotch mines on a single leaf but each mine contained only one insect, it might be the solitary oak leafminer, Cameraria hamadryadella. A mouthful, I know. The timing is right, too—the solitary oak leafminer is usually active from May through August around the Carolinas.

Solitary oak leafminers feed in individual mines but there can be several mines per leaf (left). A caterpillar can be seen mining between the leaf epidermis (right). (Photo: Dowe Winchell, Greenville-Spartanburg Airport)

There is a sister species, called the gregarious oak leafminer, Cameraria cincinnatiella. Gregarious oak leafminer differs from solitary oak leafminer in that the gregarious caterpillars feed in the same mine, creating a mine that could cover the entire leaf.

Both oak leafminer species are widespread throughout eastern North America, attacking oak of various species (but prefer white oaks). Adult solitary oak leafminers are small bullet-shaped moths with a wingspand of about 15 mm. They fold the wings over their bodies like tents. The wings are mostly white in color, with three adjoining orange or bronze and gray stripes. Caterpillars are flat, about 6 mm. long when mature, and more pointed on the rear end.

Caterpillars feed between the leaf epidermis, creating irregularly shaped blotch mines in the process. Each mine has only one caterpillar, but each leaf can support several mines. As you can see in the picture, some of the leafminers are doing quite well. But some are not (i.e. they are dead), and their mines are smaller and dark brown. Numerous mines on the leaves diminish the look of the oak tree.

Usually I don't recommend treatment for leafminers, unless the damage is severe. A few leaves got the brown blotches. So what? The trees can take it. The leaves drop but will reflush like nothing ever happened. But Dowe’s tree is a single, highly visible and valuable memorial tree. Have to protect it.

Few insecticides are registered for the management of oak leafminers. I recommended several insecticides that I think 1) are effective against caterpillars and/or 2) have translaminar or systemic activities so the active ingredients can penetrate through the epidermis into the leaf tissues and mines. I recommended foliar application with Acelepryn, Avid, Conserve and Mainspring. I didn’t recommend a neonicotinoid because I didn’t observe good efficacy of neonicotinoids against caterpillars in my previous works. Nor did I recommend products that are trunk-injected because I don't want Dowe to have to deal with extra equipment for just one tree.

Entomosporium leaf spot

Indian hawthorn and red tip photinia are dying breeds in the southern landscape. The main reason for their demise is the entomosporium leaf spot. It’s hard to find an uninfested hedge of Indian hawthorn. The rainy weeks had brought out a bumper crop of the leaf spots. You can also find this disease on loquats, pears, and other members of Rosaceae.

Entomosporium leaf spot can severely defoliate and decimate an Indian hawthorn hedge. The red leaf spots and red leaves are tell-tale sign of the disease. (Photo: JC Chong)

This is one plant disease that even I, a dummy entomologist, can identify. Heck, it even has “entomo-“ in its name; I’m obligated to get it right. Red or maroon leaf spots or blotches with brown or gray centers on Indian hawthorn—bingo! I often find plenty of black specks, which are the fruiting bodies of the entomosporium fungus, in the center of the leaf spots. Sometimes the entire leaf turns bright red.

Progression of entomosporium leaf spot on Indian hawthorn leaves. (Photo: JC Chong)

I recommend pulling out Indian hawthorns that are already severely infected, defoliated or thinned. It takes too much effort to reduce the disease severity, and the disease will not be completely gone.

If the disease is not too severe, or the plants are grown for sale, management will be necessary. For folks propagating their own cuttings, it’s important to maintain and take cuttings only from clean stock plants. In the production area, use drip irrigation (overhead irrigation splashes and disperses spores), increase plant spacing (which allows better airflow and lower humidity) and clean up debris (spores can be produced from fallen leaves).

The 2017 Southeastern US Pest Control Guide for Nursery Crops and Landscape Plantings listed 22 products from nine FRAC groups that were tested and were found to have good efficacy against fungal leaf spots. These fungicides include Spectro 90, Eagle, Banner Maxx, Bayleton, Trinity, Palladium, Cease, Camelot O, Junction, Daconil Ultrex, Clevis and Concert II, among others. Remember: always read the fungicide labels, and rotate among different FRAC groups.

No entomosporium-resistant red tip photinia is known. Austin Hagan of Auburn University and colleagues reported resistance in Rhaphiolepsis cultivars 'Indian Princess', 'Clara', 'Snow White', 'Eleanor Tabor' and 'Olivia' (Hagan et al. 2001, Journal of Environmental Horticulture 19: 43-46. Hagan et al. 2003, Journal of Environmental Horticulture 21: 16-19.). Additional cultivars, including 'Minor', 'Georgia Petite', 'Georgia Charm' and 'Pink Pearl,' were also reported by John Ruter of the University of Georgia as resistant (Ruter 2004).

Cedar-apple rust

Bossman Beytes sent me two wonderful pictures of cedar-apple rust galls. The fungus causes abnormal growth or galls on the stem, from which the teliospores are produced on telial horns (which are gelatinous when fresh, and horn-like when dried). Another wonderful display of what might happen when we have plenty of rain in a warm spring.

Cedar-apple rust is very common in eastern North America. It has a very complicated but interesting life cycle. This fungus species requires two hosts to complete its life cycle. The teliohorns usually appear in the spring (as early as late March in South Carolina) after rain. Several sets of teliohorns can be produced in a single spring. Teliospores germinate to produce basidia, which produce basidiospores. Wind carries the basidiospores to the leaves or fruits of apples, crabapples, hawthorns and quinces. The spores germinate and form yellow or orange leaf spots. The leaf spots can produce spermatia, which is a kind of spores carried by insects to other leaves on the Rosaceae hosts. The leaf spots also produce aecia, which produce aeciospores that are blown to red cedars or junipers. The rust fungi then grow on the coniferous hosts for one year, and produce teliohorns the next spring.

A wonderful display of cedar-apple rust teliohorns. (Photo: Chris Beytes)

Okay, no insect I know has such a complicated life cycle. The plant pathologists win this round.

Management is usually not necessary. The rust doesn’t kill its hosts, and the galls are pretty interesting as a conversation starter. Certainly piqued my wife’s interest this spring, although I don't think she was impressed by my pedantic explanation.

Not growing eastern red cedars and junipers, or removing them, from a few hundred yards of the desirable Rosaceae plants is one way to reduce the disease problem. Know that the spores are dispersed by wind and can travel one to three miles. Completely eliminating the problem will require removal of all red cedars and junipers within a one-mile radius, which I heard was practiced by some apple growers. Good luck with convincing your neighbors. They are perhaps more open to the idea of pruning off the galls than cutting down the red cedars.

The leaves and fruits of Rosaceae plants can also be protected from the development of leaf spots and aecia by spraying fungicides registered for rust and fungal leaf spot diseases. To the best of my knowledge, effective fungicides specifically against cedar-apple rust in ornamental production or planting are not available.

The best management approach is to grow resistant host plants. Steve Vann of the University of Arkansas has a good list of resistant crabapple and apple varieties. Consult with your local extension personnel for other resistant species and varieties.

Dogfennel in containers

The last one on my list this week is dogfennel. Y’all know that plant, right? Erect plant with fine feather-like leaves that can get rather bushy as they mature. It’s pretty distinctive.

Dogfennel is a common weed in containerized nurseries. My technician, Shawn, found the one below in a pot of dogwood I used for an ambrosia beetle trial. Look carefully and you’ll see that the dogfennel had a baby sweetgum and a cudweed for companions. Well, “had” because they are no more. Pulled out, left on the cover, desiccated.

Dogfennel is a common weed in containerized nurseries. (Photo: Shawn Chandler, Clemson University)

Dogfennel is quite difficult to get rid of with hand weeding. If the entire plant is not removed, the broken stems can resprout. A better option is to apply pre-emergence herbicides, which generally work quite well against dogfennel. Biathlon, Broadstar, Casoron, Gemini, HGH 75, Marengo, Specticle, OH2, Princep, Rout and Snapshot TG are reported as having good efficacy against dogfennel.

I wonder what’s the etymology of “entomosporium.” Does it have anything to do with insects? That’ll be my “satisfy-your-curiosity” homework for this weekend, right after I kill some arrowleaf sida in the pasture, stack the firewood and rub my dog’s belly.

Have a great weekend, y'all!

JC Chong

Associate Professor of Entomology at Clemson University

This e-mail received by 24,579 subscribers like you!

If you're interested in advertising on PestTalks contact Kim Brown ASAP!