What the ... ?

This week’s “What the … ?” creature is submitted by Mike of Greenwood, South Carolina. It looks like resin is oozing out of a hole on a pine tree. Mike also reported lots of crumbs at the base of the tree. The resin and crumbs were not there three weeks before he sent me the picture. Mike asked if his identification of the creature that caused the resin ooze was correct (which it was), and whether the trees would survive the attack.

This week’s “What the … ?” creature is submitted by Mike of Greenwood, South Carolina. It looks like resin is oozing out of a hole on a pine tree. Mike also reported lots of crumbs at the base of the tree. The resin and crumbs were not there three weeks before he sent me the picture. Mike asked if his identification of the creature that caused the resin ooze was correct (which it was), and whether the trees would survive the attack.

What do you think is making these “popcorns”? A pretty easy creature to identify. Not a greenhouse or nursery pest, but can be a big deal for folks working in silviculture and landscape.

What made the hole in pine bark surrounded by oozing resin? (Photo: Mike from Greenwood, South Carolina)

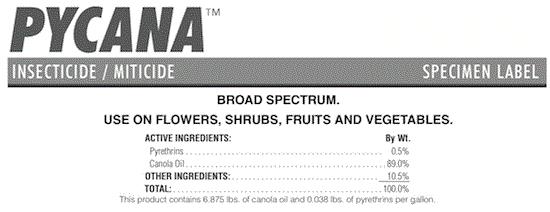

OHP introduces Pycana

Pycana insecticide/miticide is a combination of 0.5% pyrethrins and 89% canola oil, and represents an addition to OHP’s biopesticide product line. Pycana can be used in organic production, and OHP is applying for OMRI listing. REI is 12 hours, and it can be used up to the day of harvest. As of June 4, registrations have been received from all states and territories, except Arizona, California, Connecticut, Hawaii, Massachusetts, Maryland, Michigan, New Mexico, Oregon, Puerto Rico, South Dakota and Utah.

Crop uses and sites include ornamentals, vegetables, small fruits and herbs in greenhouses, shadehouses, hoophouses and nurseries. The list of target pests runs a full page, including aphids, mites, thrips, whiteflies, mealybugs, scale insects and caterpillars. Use rate is 1% solution for soft-bodied insects and mites, and 2% solution for larger and hardier insects. Pycana applied at 2% can also be used against scale insects, mealybugs and mites on dormant plants.

The combination of pyrethrins and canola oil makes Pycana a unique product. Most pyrethrin products are formulated with piperonyl butoxide to enhance pyrethrins’ effectiveness. In addition to taking the place of piperonyl butoxide as a synergist, canola oil can also act as an insecticide on its own. So, this product has two modes of action—IRAC Group 3 (pyrethrins) and unclassified (canola oil).

Pyrethrins provide quick knock down of insects but they also break down quickly under sunlight. Canola oil loses its insecticidal property when dry. Therefore, Pycana has a short residual longevity and reapplication will be needed. Label prohibits reapplication within three days except when pest pressure is high. I suggest that you rotate to another insecticide outside of IRAC Group 3 between consecutive applications of Pycana.

Phytotoxicity can occur when Pycana is mixed with or used both before and after Captan or copper compounds. Also, do not apply Pycana within 21 days of a sulfur application. Check your spray equipment and water source to make sure they are free of sulfur residue. If you are using Pycana on a plant species for the first time, I suggest a phytotoxicity test on a small group of plants before broadcast application. The label of Pycana listed several conifer species and smoke tree as oil-sensitive.

Because Pycana contains canola oil as its main ingredient, I discourage using the product in hot weather as I would for other oils. In fact, the label prohibits the use of this product when the temperature is above 90F. I would go a step further in discouraging the use of Pycana when the temperature is below 40F and on drought-stressed plants because other horticultural oils can cause phytotoxicity under similar conditions.

GrowerTalks webinars on HydraFiber and container weeds

I want to remind y’all of a couple of upcoming GrowerTalks seminars.

Jennifer Neujahr and Daniel Norden of Profile Products will talk about HydraFiber on June 28. HydraFiber Advanced Substrate is a wood fiber product that has been used as an alternative or amendment to perlite, peat, pine bark or coir in potting medium. Join the webinar to learn about this new product, growers’ experience in early trials, and whether HydrFiber is right for your operation.

Jeff Derr of Virginia Tech will talk about weed biology and management in container nurseries on July 3. Everybody has to deal with weeds. But as the cost of herbicides increases and labor becomes more difficult to recruit, weed management may become the straw that breaks the camel’s back for some operations. Come learn about the identification of some of the most common weeds in nurseries, and the most effective and efficient ways of using pre- and post-emergent herbicides.

Sign up for these free webinars at the website or click on the banner above.

How well do you spread your herbicides?

Speaking of weeds …

I just got back from a speaking tour. Of course, I talked about bugs and had some stimulating (Boy, do I got some ideas now!) discussions about redheaded flea beetles. My presentation was followed by a presentation by Joe Neal of North Carolina State University on weeds in the nursery.

I loved Joe’s presentation. The part of Joe’s presentation that really stuck with me was how spreader pattern could influence the effectiveness and cost of your weed management program, and how easy that could be corrected.

The standard application method for granular herbicides is a hand-held, hand-cranked rotary spreader. If you’d used one of these spreaders before, you know the uniformity of its spread pattern varies from person to person, day to day, and, heck, even from one row to the next. Uneven distribution or spread pattern can lead to poor management of weeds.

So, to achieve a uniform granular distribution pattern, Joe suggested:

-

Allowing 30 to 35% overlap of swath width on each side.

-

Be consistent in walking speed and cranking speed.

-

Maintain swath width between 8 and 10 ft.

-

Use only the center rudder position.

-

Refill when the hopper is about 25% full. Don’t wait until it’s completely empty.

-

Start walking and cranking the handle before opening the hopper.

-

Do not use spreaders when wind speed is above 5 mph.

-

If the spreader is calibrated to apply the full dose, then walk in the same direction among rows. Or, calibrate the spreader to apply at half dose, then walk two passes over the same path in opposite directions.

These recommendations on proper use of spreaders are the results of years of observations and experiments. Click here and check out Joe’s publication on this topic. The publication also contains more information on why Joe made these recommendations.

Answer to the "What the ... ?" quiz

The creature that caused the “popcorns” on Mike’s pine tree was the black turpentine beetle, Dendroctonus terebrans. The black turpentine beetle can be found throughout the eastern U.S., but it's more common and damaging in the South. A related species, the red turpentine beetle, Dendroctonus valens, is more widespread and damaging in the Northeast. Both turpentine beetle species are kissing cousins to the much-feared southern pine beetle, Dendroctonus frontalis, which has periodical outbreaks and causes massive tree mortality.

Mike gave me several clues to solve the mystery—the popcorns (pitch tubes is the proper term), the crumbs and the fact that most of the popcorns appeared on the lower portion of the pine tree. Kudos to Mike for solving the mystery! I merely confirmed the identification.

Black turpentine beetles, like other bark and ambrosia beetles, are borers. They bore into the wood, and in their wake, creating holes on the bark where the resin sap can ooze out, harden and form pitch tubes. They are so boring.

(BORING, as in a boring story? Y'all know what I mean? Anybody? Come on! Okay, that didn't go as well as I’d expected. Maybe that’s why I never do stand-up.)

Based on Mike’s report that the pitch tubes were not there three weeks ago, I thought the infestation was relatively recent. Often, the pitch tubes of black turpentine beetles are found on the lower portion (usually up to 6 ft. from the ground) of the tree, and lots of sawdust and broken pitch tubes can be found at the base of the tree.

Adult black turpentine beetles create tunnels on the surface of sapwood (just underneath the bark). The beetles do some structural damage to the pine trees, but that’s not why the black turpentine beetle is a major pest of pines. Like other bark and ambrosia beetles, the black turpentine beetle also introduces blue stain fungus into the phloem tissues. The blue stain fungus clogs the vascular tissues of trees and kills them. The fungus has a symbiotic relationship with the beetles—the fungus is dispersed by adult beetles, and beetle larvae feed on the fungus (not on the wood) growing within the tunnels.

Mike asked if the trees would survive the attack or if he needs to cut them down. I said I didn't know. But, based on the low number of attacks (about five pitch tubes per tree) and the attacks being in an early stage, I thought there is a good chance for the trees to survive if treatment can be applied. Bud Mayfield of USDA Forest Service and his colleagues prepared a factsheet on the black turpentine beetle, and suggested that an attacked tree will likely survive if the number of pitch tubes is less than the diameter of the tree in inches.

Although black turpentine beetles don't typically kill trees, treatment may still be warranted for lightly attacked, highly visible and valuable trees, or trees that may fall and pose significant danger to humans and structures. I typically recommend spraying an insecticide containing a pyrethroid to the trunk of the attacked and nearby trees from ground level up to about six ft. Repeated application every 10 to 14 days may be needed until no new attacks are observed.

Treatment with pyrethroids cannot kill the beetles that have already bored into the trunk, but it could prevent additional attacks. The first attackers release a pheromone to call in additional attackers. The attacked trees also release volatiles that is attractive to the beetles. If no preventive treatment is applied, more beetles will likely be attracted and attack the same tree over time.

Etymology of entomosporium

Remember I assigned myself the homework of finding out the etymology of entomosporium in last newsletter? Alyssa Collins of Penn State’s Southeast Agricultural Research and Extension Center in Manheim, Pennsylvania, immediately sent me an email and saved me the legwork.

Look at the picture of those entomosporium conidia. Don’t they look like little bugs? Their appearance makes them “super easy” to identify in the lab, as Alyssa puts it.

Entomosporium is called entomosporium because its conidia look like little bugs! (Photo: Jean Williams-Woodward, University of Georgia)

That’s awesome! Thanks for nerding out with me, Alyssa. It’s great to learn something new every day!

Have a great weekend, y'all!

JC Chong

Associate Professor of Entomology at Clemson University

This e-mail received by 24,603 subscribers like you!

If you're interested in advertising on PestTalks contact Kim Brown ASAP!