Vykenda Insecticide Receives EPA Approval

It’s finally coming, y’all!

You’ve been hearing about this new insecticide, called Plinazolin, from folks at Syngenta, me and other entomologists or industry folks for a while now. I started testing this new active ingredient in 2018 when I was still at Clemson University. The response to the question of, “When will this insecticide be introduced?” has often been, “It’s coming any time now!”

Well, it’s finally here. Syngenta announced today that its Vykenda insecticide/miticide has been granted EPA approval.

Vykenda contains isocycloseram (called Plinazolin technology by Syngenta), which is a brand-new active ingredient in IRAC Group 30. Both the active ingredient and mode of action of Vykenda are new to the ornamental market. It’s not an everyday event that we have a new mode of action, but we now have another one to rotate in our pest management program.

Isocycloseram (previously known as ISM-555) inhibits the GABA-activated chloride channel. Because GABA is the main chemical that tells a nervous system to “calm down,” the inhibition of GABA activity leads to hyperexcitation and conclusion, and eventually death of insects and mites. In another word, isocycloseram is a nerve poison.

Vykenda is registered for use on ornamental plants, Christmas trees and conifers, vegetable transplants, and non-bearing fruit and nut trees grown in greenhouses, nurseries and interiorscapes. Vykenda may be sprayed at the application rates of 4 to 10.3 fl. oz. per 100 gal. to control beetles and weevils, caterpillars, leafhoppers, leafmining flies, mites (all species), plant bugs, psyllids, spotted lanternfly, stink bugs and thrips, and suppress apple maggot, mealybugs and scale insects. (See the label for specific rates for each pest group.) Vykenda cannot be applied by drench or aerial application.

The restricted-entry interval (REI) of Vykenda is 12 hours. Personal protection equipment (PPE) for applicators and other handlers are long-sleeved shirts and long pants, shoes and socks. PPE for early entry workers are coveralls, shoes, socks and chemical-resistant gloves.

Go HERE to find more information about Vykenda, including the label, safety data sheet, information sheet and performance data. I’ll also talk a bit more about this product’s performance in January 2026. (See what I did there? Continue to subscribe and read this newsletter in 2026 if you want to know more!)

JC on the Soap Box: On the Value of Surveys

We all love to hate surveys. We have better things to do than answer questions about how we feel, what we think and what we know.

But I keep asking y’all, my faithful readers, to fill out various surveys. The IR-4 Environmental Horticulture biennial grower survey, the survey on redheaded flea beetle, the survey on mealybugs, survey this and survey that. That’s not because I want to torment you and make you so mad that you stop subscribing to this newsletter. My insistence is simply based on the fact that these surveys, when well designed, do tell us quite a bit about what troubles you're facing, what you think about a specific problem or issue, and what you’re doing or plan to do about it.

Particularly helpful are answers that aren’t expected by most researchers, experts or industry leaders. That’s because these answers help us look at things differently. One example is a survey by Drew Jeffers and his colleagues at Clemson University, published in HortTechnology, which shows us that perhaps consumers know more about pest management in the landscape than we professionals give them credit for.

I like to revisit old survey results because they tell me how much our industry and concerns have changed over time. I had such an opportunity when preparing for a talk on cut flower pests that I gave at the Great Lakes Expo last week. I’d worked with cut flower growers on and off, both domestically and in Colombia, for the past few years. But I can’t say I really know the system well.

The first thing I want to find out is what pests are bugging cut flower growers. I have my guesses based on experience, but those are just a small subset of folks in the industry and in my corner of the world. I’d like to have opinions from a larger group to back me up so I don’t look like a fool who doesn’t know what he's talking about. (Maybe I still look like one ...?)

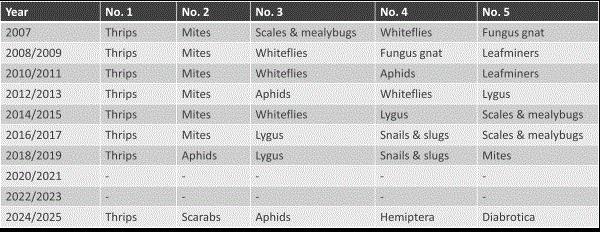

Table: The Top 5 pests of cut flowers identified by respondents to the IR-4 Environmental Horticulture Program's biennial Grower and Extension Survey from 2007 to 2025. (Source: IR-4 Environmental Horticulture Program.)

Luckily, I can simply look for the IR-4 Environmental Horticulture Program’s survey results from 2007 to 2025. If you look at the Top 5 pests of cut flowers as reported in the IR-4 surveys (see the table above), you’ll notice that thrips and mites were the top pests in 2007 and they’re still the top pests now. You may also notice that some typically outdoor pests begun to appear on the list, with the lygus bugs (mainly tarnished plant bug) first identified as a top pest in the 2012/2013 survey. Then, there were the snails and slugs. And in the 2024/2025 survey, scarabs (mainly Japanese beetle), Hemiptera (true bugs, which include lygus) and Diabrotica (corn rootworm and related species) made their appearance.

This changing list of top pests, featuring the induction of several mainly outdoor pests in recent years, tells me a story of the shifts in the cut flower industry to outdoor production and niche flower species (such as dahlia and peony). Man, I love to dig up little historical nuggets from these surveys!

So fill out a survey next time, won’t you? You never know how a snapshot of how we do things or what concerns us now may lead to new solutions in the future.

Perceptions of Biocontrol on the West Coast

Here's an example of a survey that tells us what’s going on and what folks are thinking regarding biological control on the West Coast.

Well, it’s actually two surveys. One was given to folks in the Pacific Northwest and the other to folks in California. The surveys were conducted between March 2024 and February 2025 by Surendra Dara, who has a long career at the University of California Cooperative Extension Service, was with Oregon State University at the time of the surveys and now at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. The survey results were published in the Journal of Integrated Pest Management.

In the Oregon-Washington survey, 64% of the 126 participants are growers and 11.5% are IPM practitioners in some way. About 22% of participants grow nursery crops and 13% grow ornamental crops. In the California survey, about 37% of the 209 participants are growers, 23% are IPM professionals, 8% grow ornamental crops and 6% grow nursery crops. Note that both surveys allowed folks to choose more than one option when describing their crops and didn’t specify if ornamental crops mean greenhouse production, so there are likely overlaps in participants who say they grow nursery and ornamental crops.

In the Pacific Northwest survey, 74% of the respondents are familiar with biopesticides and 63% are currently using or had used them, but only 11% were very satisfied and 45% were somewhat satisfied with the efficacy of biopesticides. When asked why they don’t use more biopesticides or why they’re dissatisfied, the most common reasons given are biopesticides are perceived to be less effective, more expensive, slower acting and require more application than synthetic insecticides, and biopesticides are more restrictive in terms of the situations the products can be used, target pest spectrum, narrow application timing or window, influence of environmental factors, a lack of residual activity, and a lack of knowledge about biopesticides and their uses.

The reasons for not using or dissatisfaction with macrobiologicals and biopesticides in California. (Figure: Surendra Dara, Journal of Integrated Pest Management 16(1): 34.)

Participants in the California survey were asked more detailed questions. Instead of asking about biopesticides in general, participants were asked about their use and perception of macro-biological control agents (predators, parasitoids, etc.) and different types of biopesticides—microbial, biofungicides, bionematicides, and botanical and other biopesticides. More than 90% of respondents are aware of macrobiologicals and all types of biopesticides, except for bionematicides (awareness of only 67%).

Many respondents have experience with these products, with use rates at more than 75% for microbial pesticides and biofungicides, 94% for botanical and mineral pesticides, 67% for macrobiologicals and 47% for bionematicides. Users of macrobiologicals, microbial pesticides, biofungicides, and botanical and other biopesticides are relatively satisfied, with 75% to 80% reporting satisfaction, but satisfaction rate is only 64% for bionematicides. The reasons for dissatisfaction given in the California survey are similar to those given in the Pacific Northwest survey.

The surveys tell me that, although folks on the West Coast know about biopesticides, there’s still a way to go in improving adoption rates and user satisfaction. Now, remember that these surveys include respondents that grow various crops. The adoption of biological control and biopesticides by berry growers, for example, may be very different to (likely much lower than) those by nursery or greenhouse growers.

Most respondents perceive biopesticides as less effective than synthetic pesticides. This perception is old and not surprising. We've also heard of other reasons for not using biopesticides. This is where educators from both extension and industry (I place myself in this category) must think about ways to fill in the knowledge gap in biological control options and their practical uses. The survey results certainly point to a hunger for knowledge of biological control and IPM.

Some food for thought for my colleagues and myself over the holiday season.

Okay—Everybody Goes Night-Night

Winter eventually comes to all places, even Back Swamp, South Carolina.

There are very few bugs left active. The mosquitoes are gone, which is a blessing. But they're replaced by black flies on calm, warm days. Warm days also wake up the hibernating stink bugs. I think we can deal with them.

Spiders are gone too, leaving behind egg sacs that contain thousands of eggs each. My nephew Isaac and I found a big ol' spider egg sac hanging from the door to Great Uncle Hugh’s shop. Spider mom had been busy during the warmer days, judging from all the dead beetles and millipedes. I bet this well-fed spider mom left behind plenty of eggs, which will hatch into thousands of spiderlings next spring.

Here, I’ll close 2025 with this fun picture of a spider egg sac. I look forward to learning with y’all in 2026.

Happy holidays. See y'all in 2026!

JC Chong

Technical Development Manager at SePRO

Adjunct Professor at Clemson University

This e-mail received by 27,847 subscribers like you!

If you're interested in advertising on PestTalks contact Kim Brown ASAP!